TRD issue 58 – July 2002

An absolutely awful month for Russian aviation: first a Tupolev Tu-154 collided with a Boeing 757 over south west Germany killing all 69 people on board the Tupolev (mainly Russian children) and the two pilots on the Boeing; then only twenty-six days later a Sukhoi Su-27 fighter crashed into the crowd at an airshow in the Ukraine killing at least 78 people.

There was an entirely different kind of tragedy for the US population when their House of Representatives passed the Homeland Security Bill.

Someone recently described me as “Dave the biker” and I must admit, I couldn’t help but feel a tiny frisson of pride. Why? What did I think he meant? Wasn’t he simply using the fact that I employ a bike for daily transport to single me out from the other Daves? Surely if that was the case, I’d have been “Dave who rides a bike”, or more straightforwardly “Dave the slaphead!”

I was definitely left with the impression that rather than making a simple external observation, he was actually expressing a far more fundamental statement about me. Assuming that was his intent, I couldn’t help wondering what the word meant to him. When he used the word ‘biker’, surely he wasn’t lumping me in with a group that encompasses everything from pizza ‘peds to R1s and beyond, because that’s a big generalisation. I’ve established that I’m into inclusion, but even a wishy-washy liberal like me wouldn’t propose that everyone who fits that bill is a ‘biker’.

My Concise Oxford Dictionary says: “Biker / n. a cyclist, esp. a motorcyclist.” So a Biker is by definition anybody who rides a two-wheeler — in particular, if they get a bit of help with the pedalling.

If my attempt to be precise proved anything, it was that some words acquire a meaning that goes way beyond the dictionary definition. If you stopped someone and asked what a biker is, most could muster a more precise description than the C.O.D. but in reality, their answers are more likely to offer an insight into their personal views and prejudices than to provide any real clarification.

To a Daily Mail reader, ‘biker’ probably conjures up a frightening image of a cross between a Hell’s Angel and Marlon Brando in The Wild One. Women around the Home Counties and shires live in mortal fear of drug-crazed animals on motorbikes. You’ve seen them peeping round their nets as you ride through their tranquil villages, telephones clutched tightly in hand ready to dial 999 as you pass. So Middle England’s response is unlikely to tell you anything useful and as far as insight into the respondent’s views go, you’d learn as much if you asked “How wonderful was the Queen Mum?” or “What percentage of black people do you think are muggers?”

So let’s ignore what Joe Public thinks because they’re notoriously unreliable. What do I think makes a biker? One thing I can state with absolute certainty is that when I bought my first bike there was no way I’d have described myself as a biker. But twenty-seven years down the line, I’d defy anybody to challenge my right to the epithet. While in my book it’s not simply a question of whether or not you ride a bike, I still can’t provide a nice neat definition. However, I’m hoping that a ramble around my experience will offer some illumination.

I bought my first bike, a TS90, when I was twenty because I was sick of the vagaries of public transport and of spending an hour and a half on a journey that would take 25 minutes on the Suzuki. At least, that was the reasoning I presented to my newlywed wife. In reality, I was struggling to maintain a reasonable voice and a poker face because the whole truth was that I’d been enchanted by bikes since I was a kid.

In the sixties, you couldn’t turn on the bank holiday news without seeing black and white images of teenagers in parkas swarming over groups of black leather-jacketed bikers. The ‘Rockers’ always seemed to be woefully out-numbered, so partly I was routing for the underdog, but more significantly, their choice of machine left the Mods out in the cold. I never understood whether all the mirrors were due to paranoia (because they knew they had targets on their backs) or to make their scooters resemble beauty salons, because the motors sounded like hairdryers. By contrast, the Rockers’ cafe racers were rolling thunder and instead of a mass of pointless frippery, they had useful additions like ally tanks, bikini fairings, and hand-milled rear-sets.

But I was never part of a biker crowd when I was young. In my teens, the closest I came was when I narrowly missed the “good-humoured” kicking my mates got from The Devil’s Henchmen (after they’d wound up the consciously crusty, back patch bikers by chanting “soap and water” at them — then failed to make good their escape). When I bought the Suzi, aside from a friend who rode his CD185 to work, I was the only person I knew who owned a bike.

A few years earlier, Pete’s Benly was the first bike I’d ever attempted to ride. In the car park at the back of the Chemistry Department in UCL, I dropped the clutch too quickly, snatched the throttle back in panic and stuffed it into the back of a VW camper! When I bought my bike, it was over three years after the debacle in the car park. I’d embarrassed myself so badly on that occasion that I hadn’t even attempted to ride one since. In 1975, there was no such thing as a CBT — as long as you had the readies and a provisional, you could ride off on anything up to 250cc. Except me, that is, because I couldn’t get the hang of the clutch.

A fourteen-year-old came out of the workshop to demonstrate and then stood by and watched as, mindful of my flying start on the Honda, I fluffed it time and again. When I finally managed to wobble for a full turn of the wheels without stalling, I tossed a wave and stuttered up the road. I stalled at the next give way line, but I was out of sight of the shop by then, so I didn’t have to listen to that acne-faced little fucker giggling again. It was the same at the traffic lights, and half a dozen more times before I reached home three miles away. For a couple of days it was a nightmare. Largely, this was because I wasn’t entirely sure if it had three or four gears, but when a friend of my brother’s took it for a spin and informed me it had five, things began to get easier.

Nevertheless, before I’d owned it for a month, I’d notched up a speeding endorsement and had my worst-ever smash. I was on a steep learning curve and I knew I needed to climb it PDQ if I was going to have any chance of retaining life, limb, and licence. Fortunately, I started a new job soon after and two of my colleagues and all of their mates owned bikes. Phil pointed out the sagging chain and showed me how to adjust it, while the others drew my attention to various shortcomings in my roadcraft (“You ride like a total wanker! I can’t understand how you stay on the bike!”).

On one of the first scorching days of 1976, while riding in short sleeves, I threw it away on a hot greasy bend, and ended up bike-less throughout the best British summer in living history. This wasn’t as a consequence of my injuries, but because my wife, who had twice seen her favourite body nastily bashed and gashed, had threatened to cut off my goolies while I slept if I so much as mentioned the B word again. It was the end of ‘77 before I felt able to broach the subject without fear of becoming eligible for harem work. I got a CG125 so it was absolutely clear that I’d bought it simply because it was the most practical way of getting from Clapton to Woolwich and back.

Yeah, right. I passed my test the following spring, and my wife and I agreed to separate later the same evening. I’m not suggesting for a minute that it was all about bikes but there’s no denying that, as last straws go, it was an extremely bulky one. Single, and with no reason to keep the pretence up, within a couple of days I’d part-exchanged the little four stroke for a Yamaha YR5.

The YR5 was the precursor to the RD350 and was a pretty rapid bike in its day. Compared to anything else I’d swung my leg across, it was wickedly fast. The handling, with standard Yamaha shocks and Teflon Bridgestones, fell some way short of awe-inspiring, but if you kept it in the sweet spot, the rasping acceleration was quite the opposite, and the twin-leading-shoe front brake was far more effective than any of the Jap discs at the time (who remembers ‘wet lag’ when it really meant something?). Besides, I could always produce sparks on roundabouts, and remember scaring more than one rider on a larger bike into submission (including a memorable joust I had right across Islington and Hackney with one of those posh new GS750s).

Throughout that summer, I fixed one thing after another on the Yamaha — then it was stolen. With my bike gone and my marriage in tatters, I ran away to America to build a new life and within days of arriving in Boston, I was offered an immaculate Norton Commando for a very reasonable price, which was just a little under my entire cash reserve. I agonised over it for a week but by that time my kitty had dwindled below the asking price, so it wasn’t an option. That was probably a good thing because, as it turned out, it was only a few weeks later that I was reduced to eating leftover pizza and boxes of donuts from a friend who owned a franchise.

I returned barely two months after my dramatic farewell, with no bike, no job, no money, and nowhere to live — except with my parents. A friend told me about a despatch company that supplied its riders with bikes and equipment, but I thought it was an urban myth. However, living back at home with mum wasn’t ideal at that stage of my life, so I rang Mercury the same day. I assumed that if they really existed they’d have a waiting list that stretched into the mid-eighties, but less than a week later I rode out of the mews as a genuine motorcycle courier.

But I knew I was bogus, because although at 24 I was among the oldest in my peer group, most of my compadres had been riding bikes for years, some since they were toddlers; whereas, if you added up the sum total of my experience, it amounted to little more than a full year and a few thousand miles. I had more front than Selfridges, so no one really noticed it, but my insecurities around my lack of pedigree nagged at me for years. In spite of the respect my new vocation generated among other motorcyclists (including British bikers who in those days were notoriously snotty about pilots of “Jap crap” — particularly two-strokes), I felt like a new boy. After three winters as a DR, I treated myself to a Ducati 900SS and even the Harley riders waved to me, but there was still that voice in my head muttering, “Fraud!”

I realise now that I set the bar unrealistically high and that I was being way too harsh with myself, but for me the word ‘biker’ has always had a special connotation. As I said at the top, I don’t normally favour exclusivity, but my parameters are considerably narrower than the dictionary definition. It doesn’t include the teenager who buys a ‘ped until he’s old enough for a Corsa. Nor does it embrace the mid-lifer who’s traded in the wife and family for a young blonde, an Audi TT and an R1.

A biker isn’t just passing through; he or she is along for the whole ride. There’s an adage along the lines of, “If you’re not a socialist in your twenties, you have no heart, but if you’re still one in your forties, you’ve no brain.” Many non-bikers would probably apply the same maxim to a love of motorcycles. But who gives a toss what they think? What do they know? I’m not suggesting that you need to have been riding for twenty years to qualify. Occasionally, young socialists grow into old ones (but not in New Labour) and it’s the same with bikers. You can fall madly in love when you’re 18, but it’s only after you’ve reached your golden jubilee that you can state with confidence that it wasn’t just a passing infatuation.

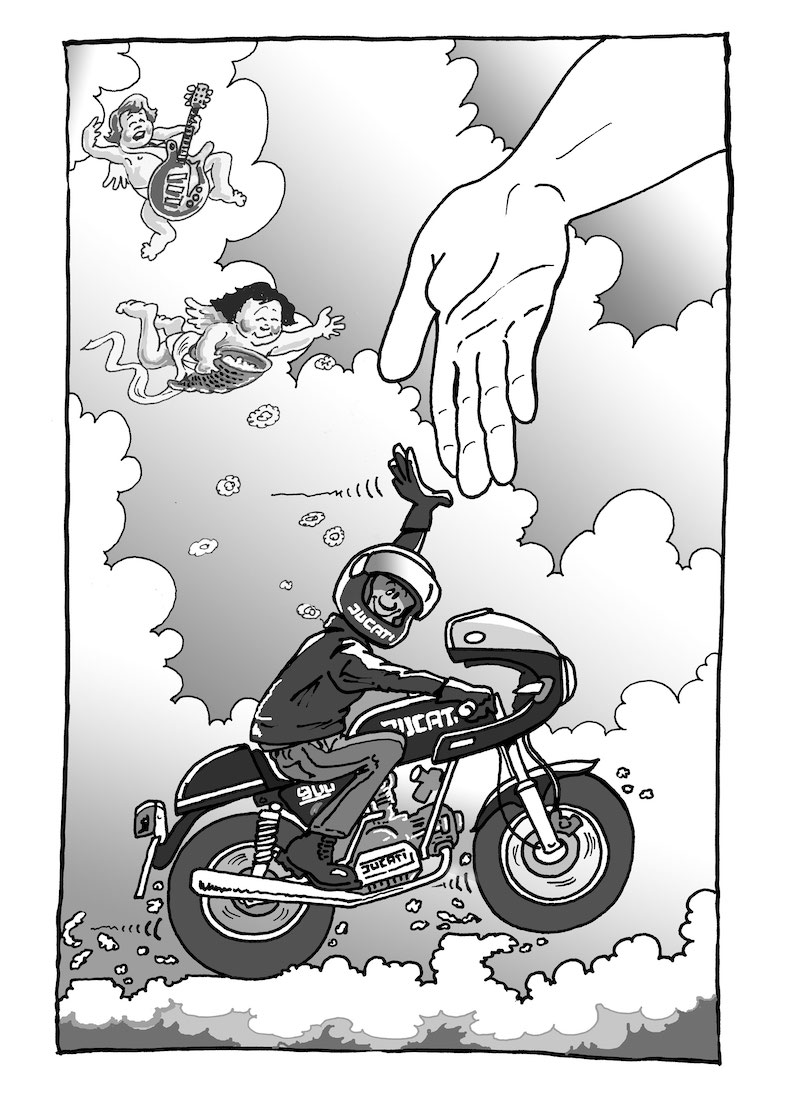

A biker is someone who rides through choice. Not because it’s the most comfortable way to transport a body, but because it can be the most magical way to carry a soul. With the possible exception of downhill skiing, motorbikes provide the purest, most intense and most accessible means of travelling at superhuman speeds. It’s not really about aspiring to get your knee down, or your front wheel up, it’s about recognising a bike’s ability to keep your spirit floating.

Bikers know that their passion will offer them a continuous stream of life-threatening situations. Recently, there’ve been many words in these pages about adrenalin and all the body’s other goodies, so I won’t revisit that ground. I’d simply add that over the centuries many volumes have been written describing the ways that close proximity to death can provide an insight into just how precious, sweet and truly wonderful life can be. When you’re on a bike, thundering along the twisting tightrope between life and death, you don’t need to have read it, you can feel it!

Then again, when the guy labelled me “Dave the biker” perhaps he didn’t even realise that mine wasn’t a ‘ped and all he meant was that I ride a bike!

Be careful out there

Carin’ Sharin’