TRD issue 32 – April 2000

The big story internationally was the snatch of a six-year-old Cuban shipwreck survivor by a Miami SWAT team, but aside from demonstrating just how bizarre life in America can be, it held little resonance for me.

The story that really stopped my clock, cut off my telephone, prevented the dog from barking with a juicy bone, and silenced the pianos, was the tragic – but not altogether unexpected – death of Ian Dury who I describe in a P.S. at the end of the following article as, “a first rate geezer and possibly the greatest ever peoples’ poet”.

Last month’s description of a low-key reunion of old Mercury bods covered the who, where and when at great length, but it scarcely touched on the WHY? Why were there still so many people willing to go to so much effort to meet up after all these years?

Nostalgia is defined in my dictionary as a “sentimental yearning for a period of the past”. If that’s the case, the halcyon days we were all aching for must have come somewhere in the first decade of the courier business proper: between about ‘72 and ‘82. Which is not to suggest that the people who turned up spend their lives longing for a bygone age – most of them probably rarely give it a thought – but once it comes up, they still find it difficult not to grin.

Of course I did mention the why at the end, but it was almost a toss-away – you could say I skimmed over it like a knee across tarmac. Excuse the trashy bike mag cliché, but in a way it sums up what Mercury was all about: riding bikes. It was that simple. We were working there because we loved bikes and they paid us passable wages (+ overtime) to ride them all day long – and then let us take them home at night. What more could a boy reasonably ask for?

In the Seventies we were living in an entirely different country. Unemployment was negligible, so just about anyone who wanted a job could get one. There was no such thing as ‘Care In The Community’ back then; if you were capable of walking out of a psychiatric hospital, you could get a job in a British Rail Red Star office. In that climate, few people went into the despatch business because it was the only way they could put a roof over their head and a jam butty on the table.

My affection for those days isn’t about our youth – we were all sorts of ages from teens to thirties – it was the industry that was young. Prior to dispatching the average biker (i.e. me) had to make do with a fun ride to work on an old bike, followed by eight to ten hours in a shop, factory, workshop or warehouse, before having another blast on the way home. The idea of being paid to ride a reasonably new bike all day was more than most lads’ wildest imaginations stretched to. The fact that we were working was almost secondary, as long as the jobs were all cleared quick enough, you were free to do whatever you wanted.

For me the job was just like a fantasy only better. Each morning when I got on the bike and called in using the helmet mounted transmitter/receiver, I got an enormous buzz. It was pot luck, anything could happen. I felt like a WWII fighter ace. Every day offered me fresh opportunities to mainline adrenaline whilst dicing with real mortal danger. Admittedly the Messerschmitts and Fokkers had been replaced by buses and Post Office vans, but the principle was the same – albeit rarely quite as terminal. I loved it; the freedom, the risk, the variety and, even then, some drop-dead gorgeous receptionists. But more important than all that, I thrived on the feeling of camaraderie.

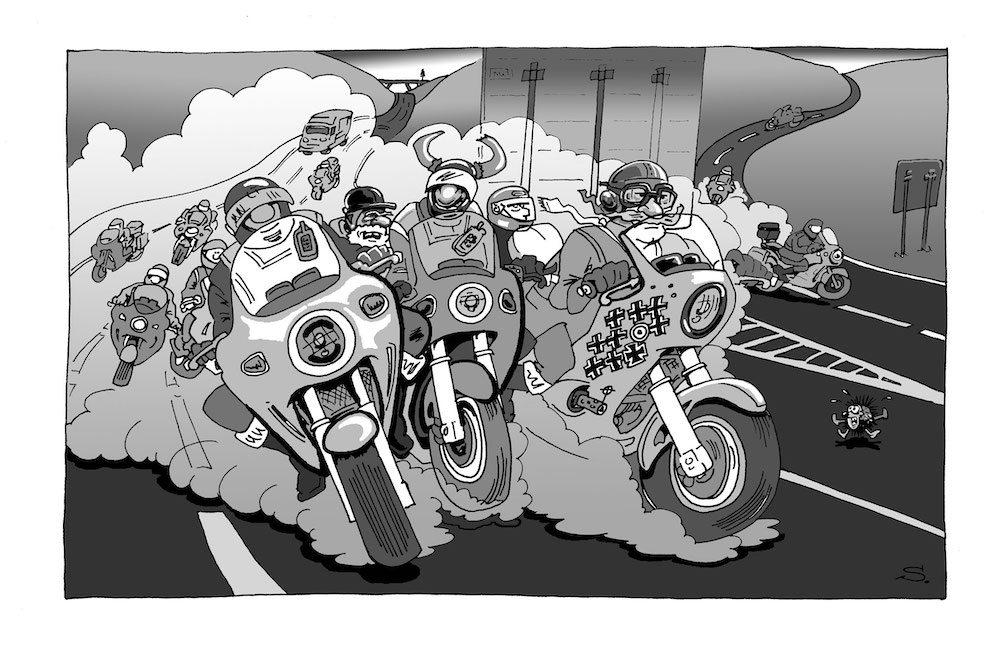

Twenty years ago, when we went out en masse we were a swarm of orange. Whether it was a party, an Evidence gig, a game of football, or a late-night curry, we shouted our common identity. At that time it would have been obvious to anyone walking down the Broadway that a large group had assembled in NW7 and they’d be in no doubt about who the mob were.

The ride home would kick off one of two ways; there was the sensible consensus and the Le Mans start, but ultimately how we began was irrelevant, because it would always end the same way – balls out. We’d scream across town in a manner that would have me tutting with disgust these days, murmuring about accidents looking for a good spot to happen.

Actually there was the third way to ride off, which was particularly popular outside The Alfred in the summer months, and that was the comical turn. These were always good for a laugh, sometimes even for the person unwittingly providing the entertainment. There was a weird mentality at Mercury in those days, which seemed to reason that as we were riding company bikes, it was OK to fuck about with them. Unfortunately this combined with a generally shared ‘anything for a laugh’ disposition that displayed a worrying lack of concern for the bodies involved.

Most of the people laughing loudly at Luigi’s were there when Woffy wheelied down Castelain Rd, bouncing off cars when his Vaselined left handlebar grip came away in his hand. But at least he managed not to dump it, so he returned to the whistles and applause of his ‘mates’. Which is more than you could say for the poor buggers who had their right hand panniers filled with water; all they got were jeers and wanker signs when they fell over pulling away.

On one occasion we tried to get a bike’s engine to run backwards. We were talking in the cafe about the fact that it was supposedly possible to bump start a two-stroke in reverse. The idea of getting someone to give it a big handful, unaware that their bike – which would be sitting in neutral with the engine running – would launch them in the wrong direction, was irresistible. When a rider turned up and dashed off to the Press centre for a slash, there were four of us laughing maniacally while desperately bumping his GT down the ramp alongside Luigi’s cafe. We dropped the bike twice, but fortunately knew nothing about timing, so we didn’t manage to pull it off. Milky’s idea, inspired by the Burt Reynolds movie Hooper, involved fixing a cable with a lot of slack to someone’s bike, while the other end was tied to a lamppost. It wasn’t followed up due to the lack of a suitable cable, rather than any sensible consideration of the potential dangers.

The zenith of the Mercury social scene was a barbecue party hosted by the Dover office in the Summer of ‘79. Around twenty bikes and half a dozen or so vans, with pillions and passengers assembled in two groups north and south of the river. I was in a courtyard in SE15, waiting with a load of others for a van driver to finish his Saturday morning run, when the crew at base in Maida Vale set off for the Blackwall tunnel. The controller kept us (and other riders who joined them en route) updated on their progress and they were well on their way before our convoy burst rudely onto Peckham High St.

In spite of some outrageous driving by our two vans, as the boys and girls from W9 sailed past Bromley-by-Bow, we were still bogged down in the Blackheath Road and looking very dodgy for our synchronised rendezvous at the Sun In The Sands roundabout. We upped the ante and took some appalling liberties, which I couldn’t begin to describe here just in case the statute of limitations hasn’t run out on them. Suffice to say, we reached the roundabout above the A102(M) flat out, with the other bunch only half way through their second circuit; so we slotted straight in and joined them for another couple of pannier scrapers before peeling off towards the coast. Anyone who’s seen the film Taras Bulba, will remember the Cossack hordes galloping across the Steppes with their numbers swelling along the way; well it was kinda like that only on a slightly smaller scale – and in orange.

The ride down was a blast, every time we reached a roundabout the bikes entered first and shut it down, only giving way to the vans. We avoided unnecessary stops by refuelling on the move; the occupants of the vans passed opened cans and bottles, unwrapped choccy bars and lit cigarettes out to the bikes, who then handed them on like relay batons (joints however were definitely not circulated in this way, as at 85-90mph, the fags were burning down at an alarming rate). The party was nearly as much fun as the ride down there – and probably just as dangerous. All round a truly memorable event.

The social and working scene all blurred into one. Work was a series of chance encounters with mates, where you’d meet, mess about for a while, then shoot off on your separate ways. Most of the regular contract runs had been clocked and any rider who fancied himself would have a tilt at the record. On a few occasions half the fleet would be poodling around, while two in-town riders going head to head were fed with every available job, simply to settle a bet on who could do most in a day. And nobody cared, because we were all on wages. Everyone else would simply spend more time larking around at base, or sitting in Shoe Lane cafe, getting regular updates on the docket count from new arrivals. Without any doubt our natural exuberance, insanity and spirit of competition earned more for Mercury than any bonus or incentive scheme they ever came up with.

I remember being pulled at work by a half-pissed TLB (the that time head honcho at Mercury) over a bill they’d received for graffiti in a posh Regent Street lift.

“Can you explain why “Dave 623” was written on the wall of the lifts in Ciros?”

“Dunno? Perhaps one of the secretaries has got the hots for me.”

“This is serious. There was loads of graffiti and I’ve received a bill for over £200. Don’t you think scrawling on walls is a bit childish?”

“Well Tony, when you put it that way… But then again, I’d hardly be working here if I was all grown up would I?”

I smiled sweetly and left, while he fumbled for an answer; but there wasn’t one really. By the Winter of 1979, Mercury provided me with a bike, Helly Hensens and a Griffin Clubman – all in bright orange; they paid for all my fuel and maintenance – and paid me £85 a week + overtime (+ a bottle of Vat 69 by way of a Christmas bonus). Which was a good wage, especially when you consider that the three-bedroom flat I shared with two other couriers cost £21 per week – between us – and beer was around 50p a pint. But just to put that in perspective, in the last full working week before Xmas 1979, I earned the company over £1,000!

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I certainly wasn’t there for the money. I was there because it was better than working and we were having it large! My relationship with Mercury was entirely symbiotic. I might have earned them a disproportionate amount of money, but the two and a bit years I spent there provided me with some of the most vital experiences – and by extension – memories of my life.

And it still makes me grin when I’m reminded of them. That’s WHY I went to the reunion. The past was bright… the past was orange!

Be careful out there

Caring Sharing Dave

P.S. Extra special credit for this month’s title. I decided on it on the 14th March – almost a fortnight before Ian Dury’s tragic death – because the song, which first charted on August 4th 1979, summed up my feelings at that time. Ian was a first rate geezer and possibly the greatest ever peoples’ poet; he’ll be sorely missed. Cheers Ian.